Old Bassett Creek Tunnel

The MWMO and the City of Minneapolis are working to remove several decades’ worth of accumulated sediment and debris from the Old Bassett Creek Tunnel.

Project Details

City: Minneapolis

Type: Capital Project

Status: Complete

Timeline: 2017–2020

MWMO Funding: $288,857

Partners: City of Minneapolis

Contractors: Minger Construction Companies, Inc.; PCiRoads

Nancy Stowe

Projects and Outreach Director

612-746-4978

Email Nancy Stowe

View Bio

The MWMO is working with the City of Minneapolis to investigate and ultimately remove several decades’ worth of accumulated sediment and debris from the Old Bassett Creek Tunnel (OBCT), which runs beneath Downtown and North Minneapolis. The multi-phase project is designed to prevent accumulated sediment and its pollutants from being mobilized and flushed into the Mississippi River. The MWMO and the city have already completed two separate phases of the cleanout effort (described below). These efforts removed a combined 1,735 tons of sediment from 1,933 feet of the tunnel. The partners continue to collaborate to look for additional opportunities to remove sediment.

Key Accomplishments

1,735

Tons TSS Removed

Two separate cleanout phases resulted in the removal of 1,735 tons of sediment.

1,933

Feet Cleared

The two cleanout phases cleared pollutants from a combined 1,933 feet of the tunnel.

2

New Access Points

Two new access hatches were created to facilitate the tunnel cleanout.

Project Background

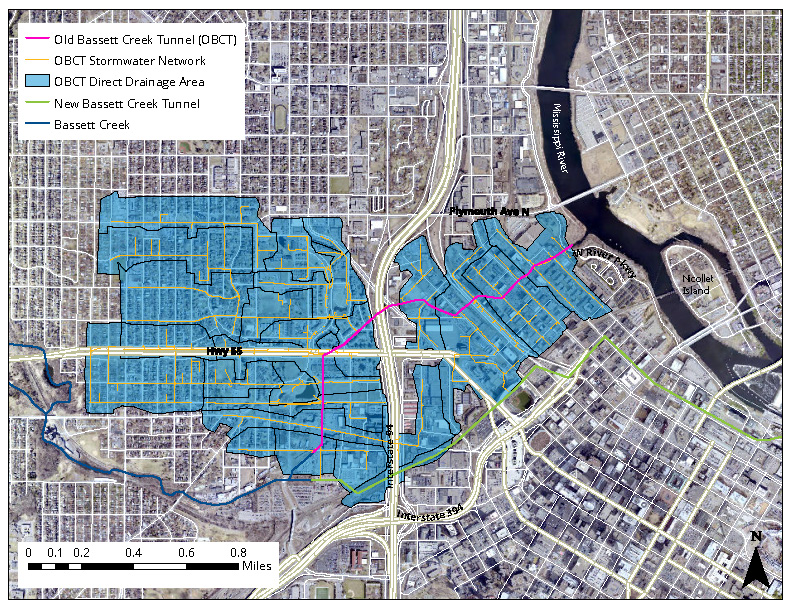

The Old Bassett Creek Tunnel (OBCT) is a 1.5-mile stormwater tunnel that extends under the Harrison, Sumner-Glenwood, and North Loop Neighborhoods of Minneapolis. Built in the early 1900s, the OBCT was designed to convey water from the historic Bassett Creek and its 40.88-square-mile watershed to the Mississippi River. The tunnel encapsulates the creek underground, and its construction helped to reduce the impact that its flood waters had on the rapidly developing area.

From 1976 to 1992, the City of Minneapolis, Bassett Creek Water Management Commission, and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers partnered to construct a new tunnel (the New Bassett Creek Tunnel) to convey waters from Bassett Creek into the Mississippi River. The new Bassett Creek tunnel was constructed to divert Bassett Creek as well as surface water runoff from I-94 and other highly developed areas of North Minneapolis to the Mississippi River. As a result, the OBCT now conveys flow from Bassett Creek only under heavy rains and high (stream) flow conditions. Under typical conditions, OBCT carries water only from the 870 acres (1.36 square miles) that drain directly into it via the city storm sewer system.

The history and oversight of the OBCT is complex. The area draining into the OBCT is overseen by two separate watershed management organizations. The Bassett Creek Water Management Commission (BCWMC) manages the area that drains to Bassett Creek. The tunnel itself, and the 870 acres that drain directly into it, are within the MWMO watershed. The MWMO has been monitoring water quality and stage at the tunnel outlet since 2008. The OBCT is owned by the City of Minneapolis, which is responsible for its operation and maintenance. As part of the Bassett Creek Flood Control Project, the city and BCWMC made an agreement to accommodate 50 cubic feet per second (cfs) of overflow from Bassett Creek to the OBCT during a 100-year rain event. Given the unique nature of the OBCT and the reduced need for using it to convey water (under most conditions), MWMO became interested in studying its function and exploring opportunities for additional uses of the infrastructure. These may include stormwater treatment or storage of stormwater for reuse.

Investigating the Tunnel’s Condition

In 2012, the MWMO and City of Minneapolis Public Works Department came together to study the OBCT. The purpose of this initial effort was to understand how the tunnel is functioning and document its condition. An inspection during fall 2012 revealed more than 3,000 cubic yards of sediment and debris deposited within the tunnel. It was also noted that limited access points into the tunnel could make removing this material a challenge.

In the spring of 2017, the MWMO and staff from Barr Engineering walked the tunnel again, this time performing a more detailed analysis of its contents. Minnesota Public Radio reporters joined the team on their walk, documenting the team’s efforts. In addition to collecting data on the material within the tunnel, the 2017 study also documented the structural integrity of OBCT and resulted in a plan on how to clean it out. Results of this work confirmed the presence of 3,900 cubic yards (approximately 6,250 tons, when wet) of sediment; laboratory testing indicated 2,500 pounds of phosphorus, 2,000 pounds of nitrogen, and hundreds of pounds of heavy metals within that sediment. In addition, the team noted significant amounts of debris. All of these materials had the potential of being mobilized and flushed into the Mississippi River. Both the city and MWMO agreed that the next step was to remove this material.

The structural inquiry performed in this project showed that OBCT is generally in “fair” condition. Barr Engineering noted substantial sediment and debris accumulation throughout the entire length of the OBCT. The City of Minneapolis is using the results of this work to plan future tunnel maintenance and improvement activities. During a street reconstruction project in the summer of 2017, the city took advantage of an opportunity to add an access point to the tunnel for future maintenance.

Cleaning Out the Tunnel

The MWMO worked with the City of Minneapolis to remove decades’ worth of accumulated sediment and debris from the OBCT. The cleanout occurred in two phases: Phase I, in the uppermost reach, was completed in 2018; and Phase II was completed in 2020.

Phase I Cleanout (2018)

This first phase of the project, completed in 2018, removed 935 tons of sediment from a 1,080-foot section of the tunnel. This section lies within the Harrison and Sumner-Glenwood neighborhoods of Minneapolis and extends 1,080 linear feet from 2nd Avenue North (tunnel inlet) to just south of 4th Avenue North, where a street reconstruction allowed the city to create a 10-foot-by-14-foot access point to the tunnel in 2018.

Because an access hatch was created, gaining access to the tunnel only required excavating a layer of roadway bituminous and removing concrete slabs from the top of the tunnel. Years of inflow from Bassett Creek, as well as other incoming stormwater pipes, led to the deposition of a large quantity of debris and sediment onto the floor of the tunnel. Sediment depths within the Phase I segment, as measured by Barr Engineering and the MWMO, ranged from 1 foot to 1.5 feet on the tunnel’s invert floor.

The Phase I cleanout was completed in the summer of 2018 with support from the MWMO’s capital funds. Minger Construction Company performed the work with oversight from the City of Minneapolis Public Works Department. Over the course of 10 days starting on June 20, 2018, the contractors removed, dried, and disposed of 935 tons of sediment and debris at an approved landfill. Skid steer loaders and a walk-behind excavator were used to move the sediment towards the access point of the tunnel. The material was then loaded into a back-hoe bucket and brought to the surface. Sediment was then place into a containment area constructed of jersey barriers that allowed for water to decant from the sediment before being hauled away.

At least two significant rainfall events during the time of the clean-out added to the complexity of removing the material. By-pass pumps and hoses were used to move as much water as possible downstream of the cleanout segment. Silt fencing helped slow the discharge and allow sediment to settle out of the water. After removal, sediment was stored above ground for at least 24 hours to allow dewatering before off-site disposal.

The project helped the city understand the best methods for effectively and efficiently cleaning out the OBCT while minimizing costs and any disruption to nearby residents, businesses, and pedestrians.

Phase II Cleanout (2020)

This second phase of the project, completed in 2020, removed 800 tons of sediment from an 853-foot section of the tunnel extending from 4th Avenue N to Olson Memorial Highway. This was identified as the section with the most accumulated sediment in the OBCT, with sediment depths ranging from 5 inches to 27 inches. The MWMO funded a contractor to remove, haul, and dispose of accumulated sediment and debris at an approved waste facility.

Initiating Phase II required the City of Minneapolis to install a new access hatch under Fifth Avenue North, just east of Van White Memorial Boulevard. The invert of the tunnel in this location is approximately 14 feet below ground, and takes various shapes as parts of the tunnel have been built or replaced over time. Some of the original sections are made out of brick and curved, with a maximum height of 7.5 feet, so the contractor was limited to using walk behind skid steers as equipment that was lowered into the tunnel to push the sediment towards the entrance. A crane lifted the sediment out of the access point and it spread out to dry before hauling it away.

Future Potential Cleanout Projects

The MWMO intends to pursue additional cleanout phases with the city. Future work will include both additional sediment and debris removal, as well as monitoring, to observe the rate and nature of how sediment begins to accumulate back within the tunnel. There is a point in the tunnel where fluctuating water levels in the Mississippi River actually cause the tunnel to receive backflow to a certain reach, so the MWMO does not intend to clean out the entire 7,900 linear feet.

Future cleanout phases will be dependent on location and creation of access hatches, as well as other site access constraints, such as how the tunnel becomes incrementally deeper below ground as you move further downstream. The MWMO also intends to monitor the amount of time it would take for the tunnel to accumulate sediment again, to help determine the potential frequency of tunnel cleanouts needed.

More Photos