News / January 30, 2024

Is Water Quality Improving in the Mississippi River?

“How clean is the Mississippi River?”

It’s one of the most common questions we receive at the MWMO, and a deceptively tricky one. The answer depends — on the day, the location, and what we’re measuring.

Here’s the short answer: In the Twin Cities, water quality in the Mississippi River has improved dramatically over the last century. But while we’ve continued to reduce some types of pollutants, others stubbornly persist — and new threats are also emerging.

The longer answer is, of course, more complicated. Let’s start with the basics: We care about pollution in the river because it negatively impacts aquatic life, habitat, and, ultimately, the people who use the river. The MWMO is one of many organizations that help monitor the water quality of the river and work to protect and restore it.

Water quality can vary widely over the 2,340-mile length of the Mighty Mississippi. For our purposes, we’ll focus on the health of the river as it runs through the Twin Cities Metropolitan Area.

Water Quality in the River: What’s Improving and What’s Not

Recent decades have seen significant reductions in some types of pollutants and increases in others. Here’s a brief summary of some of the most significant trends of the last 40–50 years, as documented in several reports by government agencies and nonprofits (see below).

What’s Improving:

- Bacteria. Efforts to separate stormsewers from sanitary sewers significantly reduced the presence of dangerous bacteria such as E. coli in the river. This reduction means less potential for illness in humans and pets.

- Sediment. Total suspended solids (TSS) have been reduced in the river as it flows through our watershed — in part due to slowing urban and suburban development rates. Sediment impacts visibility, which harms aquatic habitat and recreation.

- Phosphorus. In recent decades, improvements in wastewater treatment, a ban on phosphorus fertilizer for lawns, and green stormwater infrastructure have reduced phosphorus loading, reducing harmful algae growth.

What’s Not Improving:

- Nitrate. Fertilizer used in agricultural production is the main culprit in nitrate pollution in the river, and the problem is slowly worsening. Nitrate fuels algae growth and contributes to the Gulf of Mexico’s dead zone.

- Chloride. The toxic chemical ingredient in road salt continues to accumulate year after year in our waterways. It’s harmful to aquatic life and corrodes infrastructure.

- Emerging contaminants. Microplastics and a wide variety of unregulated chemicals are known to be present in the river, and the science around them is still evolving. Their impacts vary, but they are often harmful to aquatic life and humans.

It’s important to remember that pollution always travels downstream. The Mississippi River takes in water from an area of approximately 19,680 square miles — nearly a quarter of the entire land mass of Minnesota — before it reaches the boundaries of the MWMO. So we’re always impacted by what happens to the north of us.

Likewise, our urban pollutants travel south, impacting communities downstream of us. Pollutants tend to accumulate as they go, eventually causing severe impacts in trouble spots like Lake Pepin and all the way to the Gulf of Mexico.

How We Got Here: A Brief History of Pollution and Restoration in the River

The last several decades have shown significant overall improvement in local water quality. But to understand where we are today, a bit of history is in order.

Prior to European settlement and industrialization, the river provided an abundant and healthy ecosystem for the people who lived here. This once-healthy landscape underwent dramatic changes as the new settlers arrived and displaced the native communities. The MWMO recognizes its presence on the traditional and treaty land of the Dakota people, alongside the Ojibwe people, who are the Indigenous inhabitants of the region now known as Minnesota and still live here to this day.

St. Anthony Falls offered a power source for timber and flour mills, which spurred rapid industrialization and population growth in Minneapolis. Residents needed a place to dump their sewage, so the city constructed sewers to pipe it into the river to be carried away. But the construction of the first lock and dam in 1917 interrupted the natural “flushing” of the river and caused sewage to build up, creating noxious “rafts” of floating human waste.

Water quality in the river reached a low point in the 1920s and ’30s. By that point, fish life was documented to be virtually extinct between Minneapolis and La Crosse, and communities along the river suffered frequent outbreaks of disease. A key turning point came in 1938, when the first wastewater treatment plant opened in St. Paul. Within two years, fish populations began to rebound.

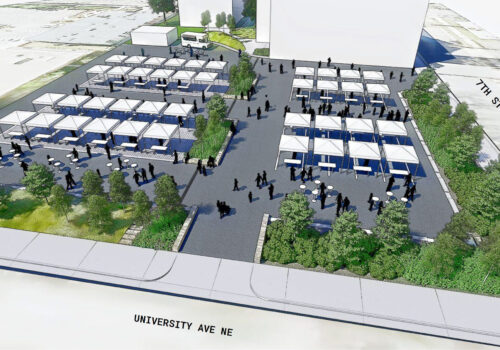

What followed was a century of reforms, regulations and technological innovation. Wastewater treatment methods improved, and the 1972 Clean Water Act provided a new set of tools for officials to set and meet water quality standards. Beginning in the 1980s, sanitary sewers were separated from stormsewers, and a state law spurred the creation of local organizations like the MWMO, which promoted green stormwater infrastructure (GSI) to help manage urban runoff.

These policy changes, implemented over many decades, led to a drastic improvement in water quality in the river. Today, a broad coalition of public, private and nonprofit partners are working to continue to reduce pollution and enhance the river’s ecology. The MWMO is one of them, and we look forward to helping to build the infrastructure and programs that will contribute to the next 100 years of river restoration and protection.

Learn More

- Metropolitan Council Regional River Water Quality Report (2015)

- State of the River Report (2016)

- Upper Mississippi River Basin Association “How Clean is the River?” Report (2023)*

- 100+ Years of Water Quality Improvements in the Twin Cities (2008)

*This report focuses on areas of the river that are south of the Twin Cities.